Mount Mantap is the world’s only active nuclear test site. Most other nuclear states long ago gave up such explosions in a coordinated effort to end arms races and their dangerous and costly spirals of military action and reaction. In North Korea, the test devices are buried deep inside tunnels bored through solid rock far below Mount Mantap’s peaks, creating field labs for nuclear experiments. The nearest major city, Chongjin, is situated about 50 miles to the northeast. The tunnels for the North’s tests are excavated just over halfway up Mount Mantap, which rises to a height of 7,234 feet. The bomb is placed at the end of the tunnel, which gets partly backfilled to prevent radioactive leakage, and then detonated in the test. To pinpoint the geographic site of the nuclear blasts, experts rely on the kind of seismologic data used to track earthquakes. Similarly, each of the North’s detonations has generated shock waves that register around the globe. Top – Photo: Left: Jan. 22, 2017 – Top arrow points to Entrance to north tunnel – Bottom arrow points to Water drained from tunnel Right: March 28, 2017 – Arrow points to Water continuing to be pumped out. Bottom – Map: The Divided Korean Peninsula

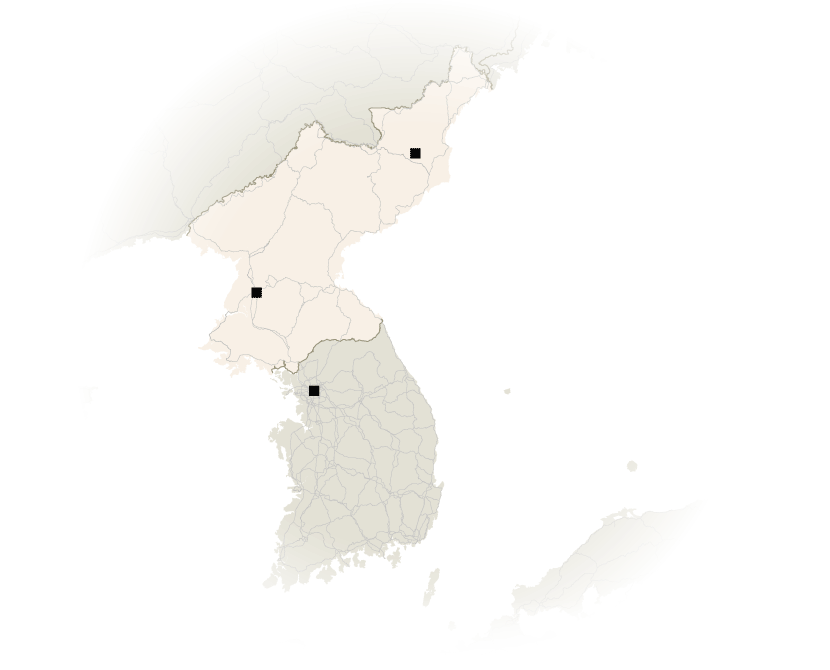

The Divided Korean Peninsula

China lies to the North, Japan to the East

Northernmost Pinpoint — Punggye-ri, North Korean nuclear test site

Middle Pinpoint — Pyongyang, capital of North Korea

Southernmost Pinpoint — Seoul, capital of South Korea

——————————–

New satellite images suggest that North Korea might soon conduct another underground detonation in its effort to learn how to make nuclear arms —

its sixth explosive test in a decade and perhaps its most powerful yet.

North Korea’s nuclear tests have grown steadily more destructive,

and the country continues to pursue its longtime goal of putting a nuclear warhead on an intercontinental missile capable of reaching targets around the globe.

The US recently ordered an aircraft carrier and other warships toward the Korean Peninsula —

a show of force intended to discourage the North from testing a nuclear weapon.

While examining satellite imagery, experts have observed a wide range of activity at

Mount Mantap, a mile-high peak where North Korea conducts its nuclear tests.

Beneath the mountain, a system of tunnels has been excavated for the past five detonations of the North’s nuclear bombs.

Big debris pile suggests the possibility of a much larger detonation

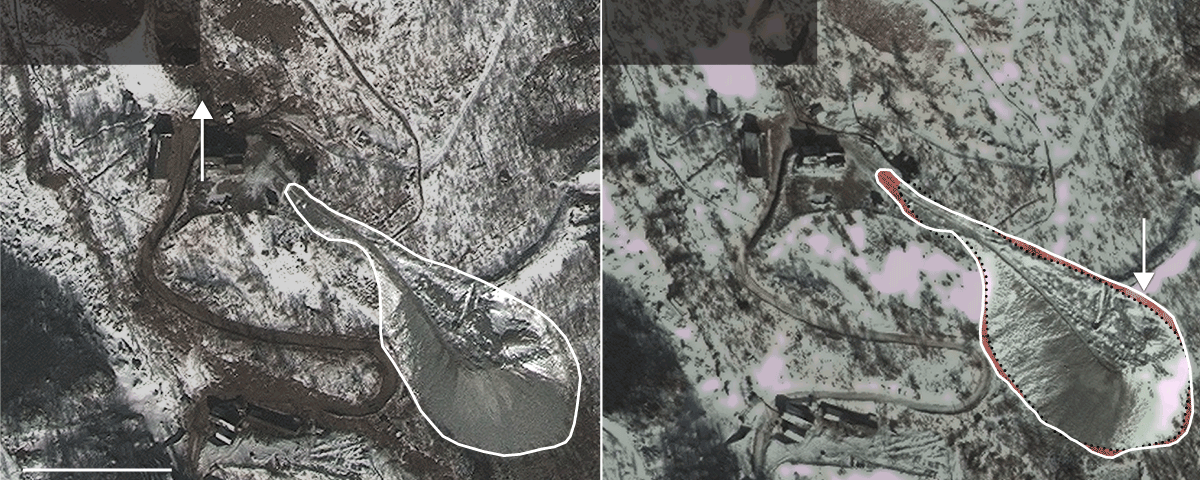

Since late 2013, piles of rocky debris from the excavation of the site’s North tunnel system have grown quite large — now big enough to cover a football field, and quite high.

It’s the largest pile ever observed there.

Work on the excavation has recently slowed, quite likely signaling readiness for the next detonation.

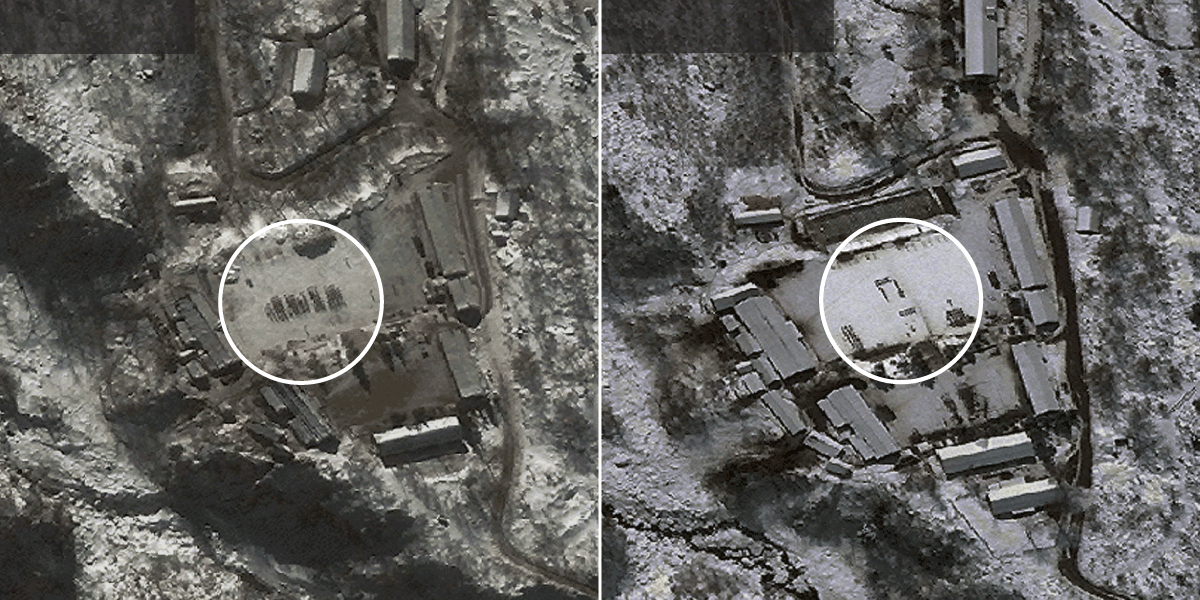

Left: Satellite Photo from Jan. 5, 2017 – Arrow points to the entrance to the North Tunnel

Right: Satellite Photo from Jan. 22, 2017 – Arrow points to additional debris

So too, observers of the test site have recently noted a lot of water being pumped out of the North tunnel system –

presumably to prevent washouts and keep it dry for test instrumentation.

Groundwater is often a problem in tunneling as it can slow progress, weaken structures and cause shorts in electrical gear.

Left: Jan. 22, 2017 – Top arrow points to Entrance to north tunnel – Bottom arrow points to Water drained from tunnel

Right: March 28, 2017 – Arrow points to Water continuing to be pumped out

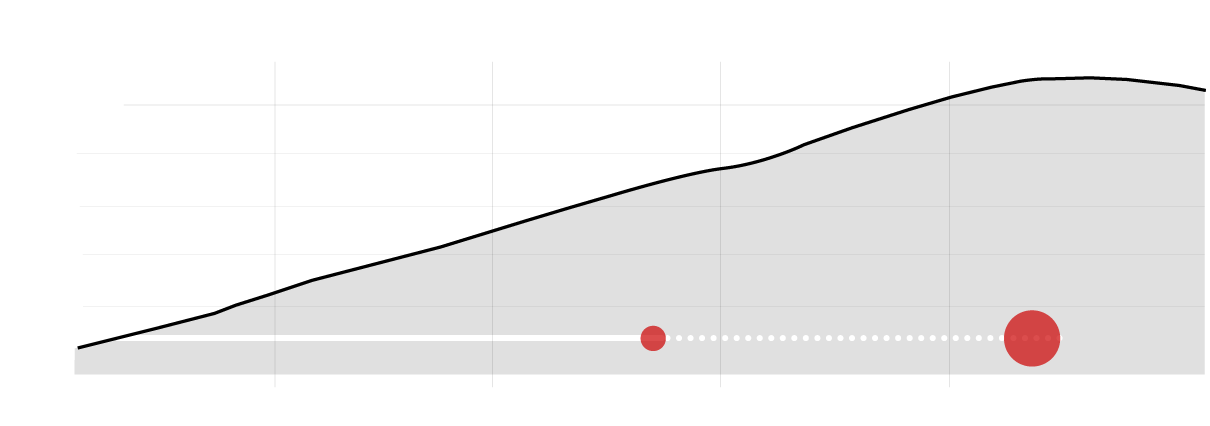

Scientists at the Los Alamos weapons lab who have studied images of the large debris pile recently concluded that

Mount Mantap could withstand a nuclear explosion of up to 282 kilotons –

roughly 20 times stronger than the Hiroshima blast.

Previously, the largest detonations were in the Hiroshima range.

No one outside of North Korea knows for sure what could take place or how big the blast might be.

It’s a guessing game — a sophisticated one for Washington’s intelligence agencies,

less so for civilians armed only with unclassified information.

Either way, it’s a detective story full of clues, questions and a protagonist with a clear motive.

Experts in satellite imagery, military analysts around the world, and geologists and physicists

track progress at the remote site mainly through

- the observation of tunneling,

- building construction,

- truck movements

- and, though harder to see, personnel moves.

Seismic activity helps pinpoint North Korea’s detonations

Mount Mantap is the world’s only active nuclear test site.

Most other nuclear states long ago gave up such explosions in a coordinated effort

to end arms races and their dangerous and costly spirals of military action and reaction.

In North Korea, the test devices are buried deep inside tunnels bored through solid rock far below Mount Mantap’s peaks, creating field labs for nuclear experiments.

The nearest major city, Chongjin, is situated about 50 miles to the northeast.

The tunnels for the North’s tests are excavated just over halfway up Mount Mantap, which rises to a height of 7,234 feet.

The bomb is placed at the end of the tunnel, which gets partly backfilled to prevent radioactive leakage, and then detonated in the test.

To pinpoint the geographic site of the nuclear blasts, experts rely on the kind of seismologic data used to track earthquakes.

Similarly, each of the North’s detonations has generated shock waves that register around the globe.

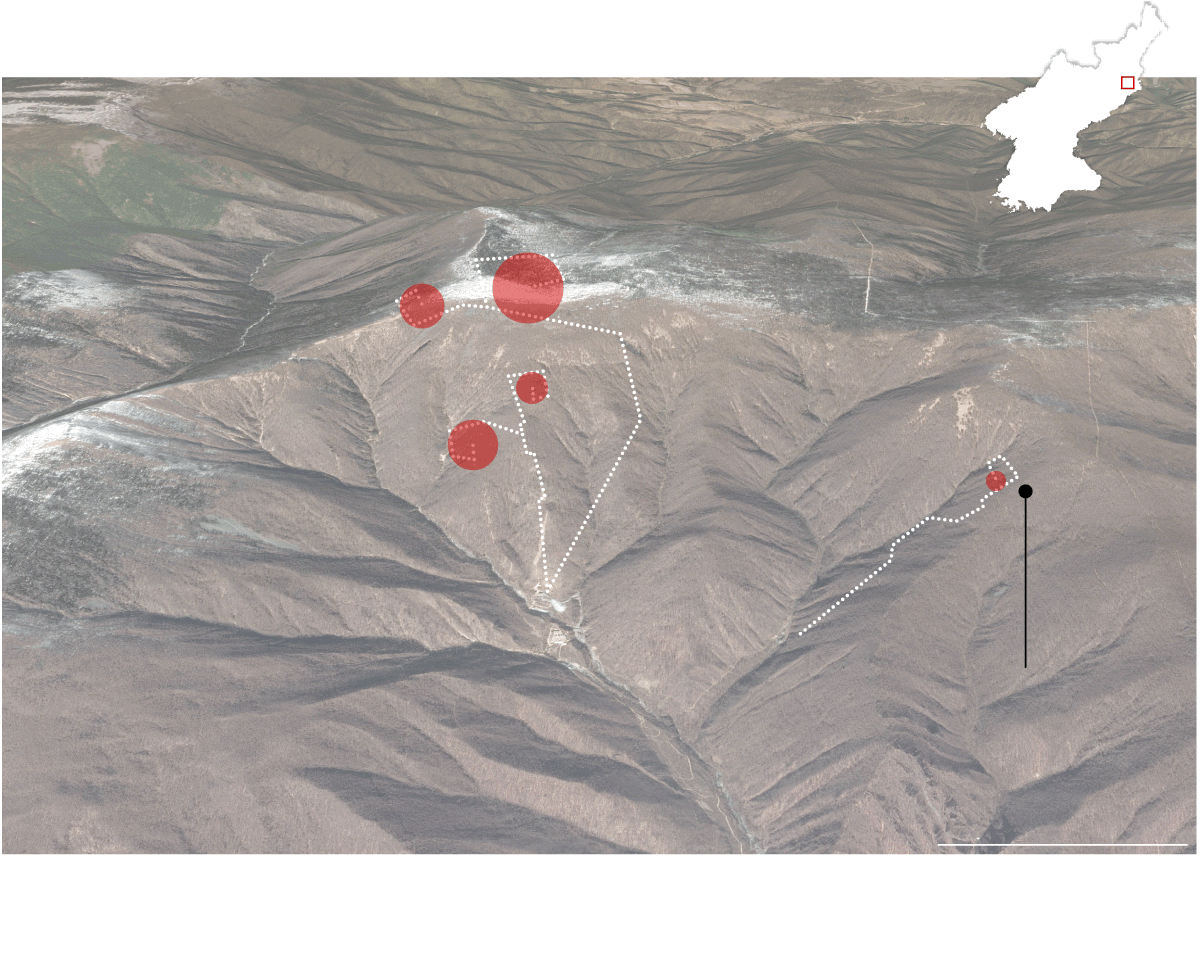

MT. MANTAP — Slope from North Tunnel Entrance at ~5000 feet to Top at 7,250 feet

First smaller red dot — Test 2 — About 1,600 feet deep — Magnitude 4.5

Second larger red dot — Test 5 About 2,625 feet deep — Magnitude 5.3

Satellite Image by CNES / Astrium via Google Earth | Magnitude data from the Nuclear Threat Initiative and USGS

Note: Tunnel system based upon an analysis by Frank Pabian and Siegfried Hecker.

Experts say the North’s tunnel system will quite likely play a significant role in future testing because

- it is the busiest area at the Punggye-ri nuclear test site,

- has a conspicuous perimeter fence

- and has the largest amount of protective rock directly overhead.

Several independent teams, including ones from China, South Korea, Norway and the United States, have gathered seismic readings from the North’s bomb tests.

In addition, a world body known as the the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty Organization, based in Vienna, Austria, operates a sprawling network of global sensors.

Last year, a team of South Korean scientists confirmed a test’s exact location within Mount Mantap

by studying data from a radar satellite that detected subtle elevation changes on the mountain’s surface.

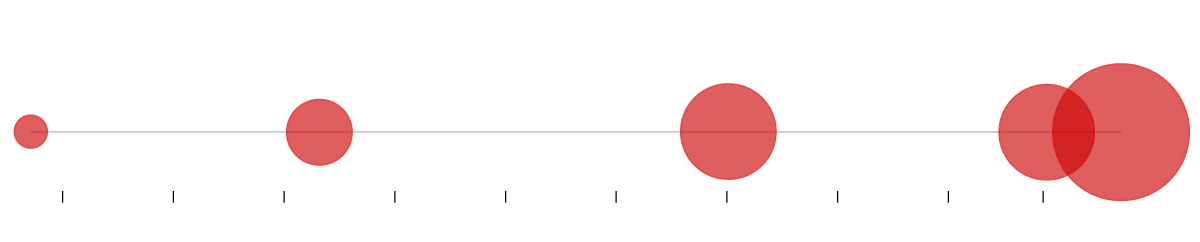

So far, North Korea’s nuclear tests have grown more destructive.

Circles sized by destructive power:

2 kilotons – 2006

8 kilotons – 2009

17 kilotons – 2013

17 kilotons – 2016

35 kilotons – 2017

Note: Destructive power numbers represent worst case estimates.

The North has shown technical savvy in pacing its nuclear tests to increase the amount of time for bomb makers to conduct detailed analyses of the blasts and learn from mistakes.

“They’ve done five tests in 10 years,”

said Siegfried S. Hecker, a Stanford professor who once directed the Los Alamos weapons laboratory in New Mexico, the birthplace of the atomic bomb.

“You can learn a lot in that time.”

In contrast, he added, India and Pakistan conducted a rush of nuclear detonations in May 1998 in what experts called a blitz of saber rattling.

“They couldn’t have learned much,” Dr. Hecker said.

North Korea may be focused on increasing the power and range of its nuclear weapons

North Korea’s past tests are thought to have centered on mastering a simple type of atomic bomb, known as an implosion device.

Some of the tests may have featured “boosted” atomic bombs, however —

meaning that an injection of tritium, a radioactive form of hydrogen, could have increased their destructive power.

All such fuels, known as thermonuclear, need the high heats from an exploding atom bomb for ignition.

“It’s possible that North Korea has already boosted,” said Gregory S. Jones, a scientist at the Rand Corporation who analyzes nuclear issues.

Like other experts, he pointed to the nation’s two nuclear detonations last year as possible tests of small boosted arms.

As signs of the North’s interest in boosting, experts cite modifications to a reactor that could make tritium,

as well as construction of a plant that could gather up the radioactive gas.

Boosted arms can raise the destructive power of atomic blasts or greatly reduce their need for atomic fuel.

That savings can significantly lighten and shrink the resulting arms, making them easier to hurl over long distances.

Boosting is considered a main step to scaling down warheads so they can fit atop intercontinental missiles.

Nine countries possess nuclear arms, most having advanced over time from making simple atom bombs to advanced hydrogen bombs.

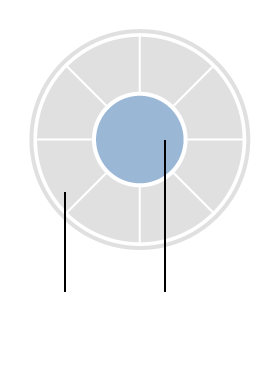

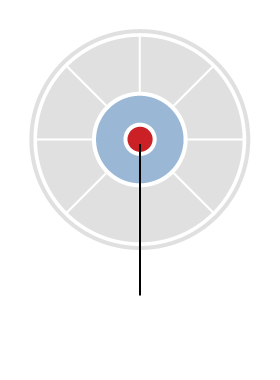

Nuclear experts say North Korea’s program is at an intermediate phase of development — somewhere between stages one and three.

The secret to achieving more destructive power is to raise the amount of thermonuclear fuel that an exploding atom bomb can ignite.

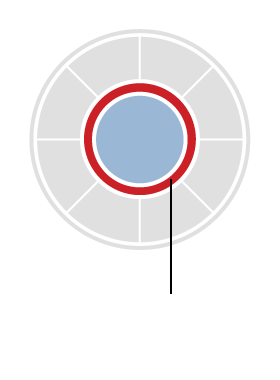

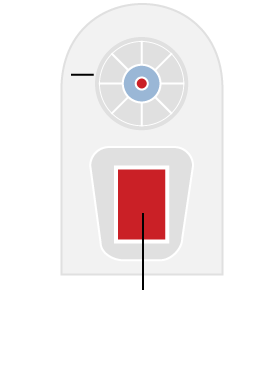

STAGE 1

Implosion Atom Bomb — Uses conventional explosives to compress and ignite atomic fuel

Destructive power = 1 Hiroshima

Pale Blue – Explosive layer

Dark Blue – Atomic fuel

STAGE 2

Boosted Atom Bomb –Uses a bit of thermonuclear fuel inside the atomic core

Destructive Power = 3 Hiroshimas

Red core = Thermonuclear gas

STAGE 3

Layered Atom Bomb – Uses more thermonuclear fuel outside the atomic core

Destructive Power = 25 Hiroshimas

Red circle = Solid thermonuclear fuel

STAGE 4

Hydrogen Bomb – Uses lots of hydrogen fuel that the nearby atom core ignites

Destructive power = 1,000 Hiroshimas

Red rectangle = Solid thermonuclear fuel

Note: Destructive power for each stage is based on early tests in the US and USSR, not on current stockpiles.

Experts say the likelihood of North Korea making strides in its nuclear program has risen with the recent evidence the nation tried to sell excess lithium-6,

which is the main ingredient for making thermonuclear fuels, including tritium.

So too, satellite images of the mountainous test site reveal the digging of the deep tunnel system,

which could allow the detonation of a larger device.

A gathering at the remote site is considered a strong sign

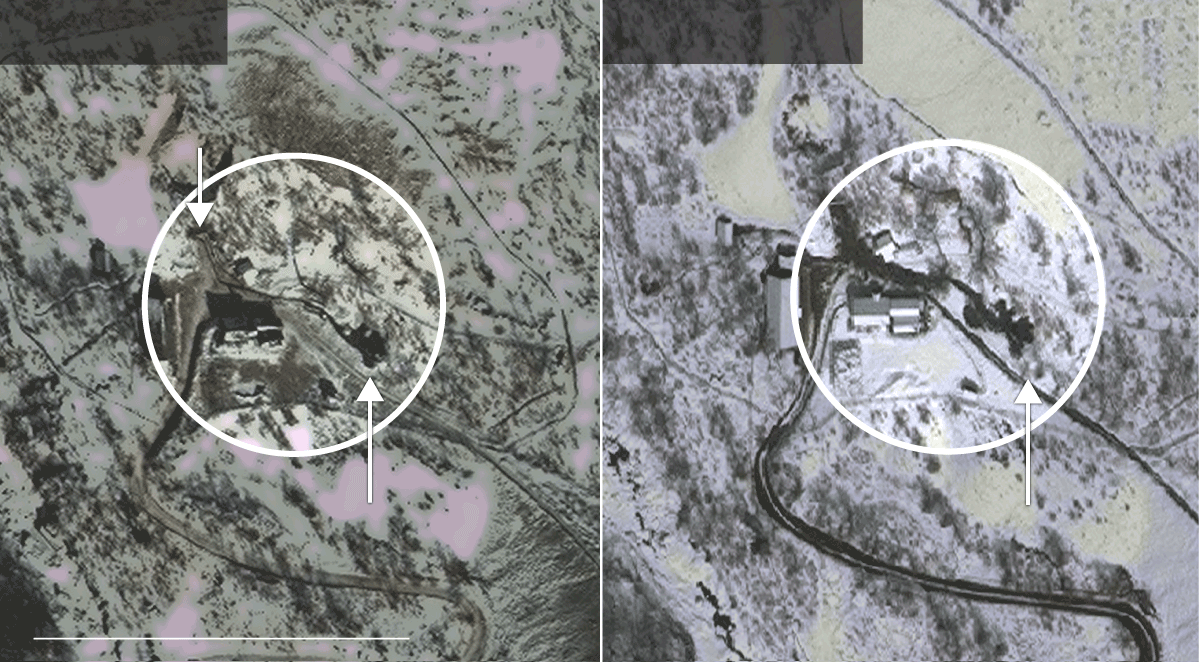

On March 28, a satellite image showed people gathered in front of an administrative building at the test site.

The last time such a large group was observed was on Jan. 4, 2013, a little more than a month before North Korea’s third nuclear detonation.

Left: Jan. 4, 2013 — People in parade formation

Right: March 28, 2017 — People gathered in formation

Experts see the recent gathering as yet another sign the North may be getting closer to detonating a device in its increasingly long series of nuclear tests.

“The fact these formations can be seen suggests that Pyongyang is sending a political message that the sixth nuclear test will be conducted soon,”

wrote Joseph S. Bermudez Jr., and Jack Liu, experts at 38 North, an analysis group that closely tracks North Korea.

“Alternatively, it may be engaged in a well-planned game of brinkmanship.”

Source: North Korea May Be Preparing Its 6th Nuclear Test – The New York Times