As China scrambles to recover from global hack, risks of dependence on unsanctioned software clear. After Snowden leaks, Beijing accelerated push to develop Chinese-branded software & hardware that would be harder to breach. In 2014, Microsoft cut off support for Windows XP, still widely used by government & Chinese companies. Official news agency Xinhua said such corporate behavior could be considered anticompetitive. Prestigious universities like Tsinghua & Beijing were affected by ransomware, as were major companies like China Telecom & Hainan Airlines. Securities regulator said it had taken down its network to try to protect it & country’s banking regulator warned lenders to be cautious when dealing with malicious software. Many users did not update software to get latest safety features because of fear their copies would be damaged or locked. Police stations and local security offices reported problems on social media, while students reported being locked out of final thesis papers. Below, PetroChina pump in Beijing. “Wanna Cry” caused electronic payment systems at gas stations run by the state oil giant to be cut off for much of the weekend.

China is home to the world’s largest group of internet users, a thriving online technology scene and rampant software piracy

that encapsulates its determination to play by its own set of digital rules.

But as the country scrambles to recover from a global hacking assault

that hit its companies, government agencies and universities especially hard,

the risks of its dependence on unsanctioned software are becoming clear.

Researchers believe large numbers of computers running unlicensed versions of Windows probably contributed to the reach of the so-called ransomware attack,

according to the Finnish cybersecurity company F-Secure.

Because pirated software usually is not registered with the developer,

users often miss major security patches that could ward off assaults.

It is not clear whether every company or institution in China affected by the ransomware,

which locked users out of their computers and demanded payment to allow them to return, was using pirated software.

But universities, local governments and state-run companies probably have networks that depend on unlicensed copies of Windows.

Microsoft and other Western companies have complained for years about widespread use of pirated software in a number of countries that were hit particularly hard by the attack.

A study last year by BSA, a trade association of software vendors, found that 70% of software installed on computers in China was not properly licensed in 2015.

Russia, at 64%, and India, 58%, were close behind.

Zhu Huanjie, who is studying network engineering in Hangzhou, China, blamed a number of ills for the spread of the attack,

including the lack of security on school networks.

He said piracy was also a factor.

Many users, he said, did not update their software to get the latest safety features because of a fear that their copies would be damaged or locked,

while universities offered only older, pirated versions.

“Most of the schools are now all using pirate software, including operation system and professional software,” he said.

“In China, the Windows that most people are using is still pirated. This is just the way it is.”

On Monday, some Chinese institutions were still cleaning computer systems jammed by the attack.

Prestigious research institutions like Tsinghua University were affected, as were major companies like China Telecom and Hainan Airlines.

China’s securities regulator said it had taken down its network to try to protect it,

and the country’s banking regulator warned lenders to be cautious when dealing with the malicious software.

Police stations and local security offices reported problems on social media,

while university students reported being locked out of final thesis papers.

Electronic payment systems at gas stations run by the state oil giant PetroChina were cut off for much of the weekend.

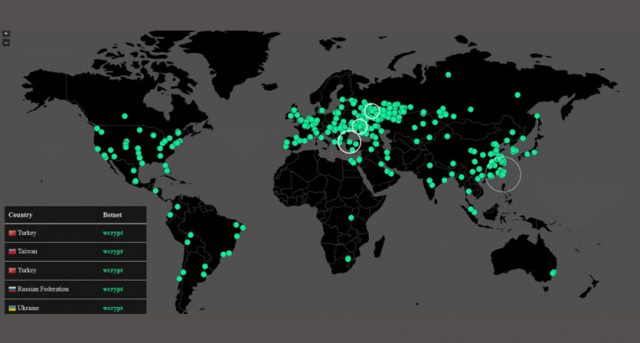

Over all, according to the official state television broadcaster, about 40,000 institutions were hit.

Separately, the Chinese security company Qihoo 360 reported that computers at more than 29,000 organizations had been infected.

At China Telecom, one of the country’s three main state-run telecommunications providers,

a similar scramble occurred over the weekend,

according to an employee who was not authorized to speak on the matter.

When a company-provided software patch did not work, the employee was told to use one from Qihoo 360,

which supports pirated and out-of-date versions of Windows, the person said.

A spokesman for China Telecom did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

On Monday, the main internet regulator, the Cyberspace Administration of China, quoted an unnamed person in charge of internet security saying that

the ransomware was still spreading but the speed of transmission had slowed.

It said that regulators overseeing banks, schools, the police and other groups had given orders to stop the risk

and that it had instructed users on how to avoid exposure.

Using copied software and other media has become embedded in China’s computing culture,

said Thomas Parenty, founder of Archefact Group, which advises companies on cybersecurity.

Some people are under the impression that using pirated goods in China is legal,

while others are simply not used to paying for software, he said.

Parenty cited an instance when he was working at the Beijing office of an American client.

“It turned out every single one of their computers, all the software, was bootlegged,” he said.

The twin problems of malware and the unwillingness to pay for software are so ingrained that they have led to an alternative type of security company in China.

Qihoo 360 built its business by offering free security programs; it makes money from advertising.

The issue has led to political battles between Microsoft and the Chinese government.

In a bid to get more organizations in China to pay for their software,

Microsoft, which is based in Redmond, Wash., has tried education and outreach.

It has also stopped distributing Windows on discs, which are easy to copy.

One effort in 2014 put it at loggerheads with Beijing.

At that time, Microsoft cut off support for Windows XP, an operating system that was about 14 years old

but that was still widely used by the government and by Chinese companies.

Many in China complained that the move showed that the country still relied on decisions made by foreign companies.

An article by the official news agency Xinhua said that such corporate behavior could be considered anticompetitive.

Microsoft later agreed to offer free upgrades and reached a deal with a state-run company that often works for the military to develop a version that catered to China.

The Chinese government has been less focused on software piracy — and more on building local alternatives to Microsoft.

After leaks by the former intelligence contractor Edward J. Snowden about American hacking attacks aimed at monitoring China’s military buildup,

leaders in Beijing accelerated a push to develop Chinese-branded software and hardware that would be harder to breach.

For now, however, much of China relies on Windows.

And for all of the impact of the weekend’s cyberattack, Parenty said

he did not think that there would be a big effect on attitudes toward pirated software.

“The only way I see this changing things is if the central government decides there is a risk to critical infrastructure from this threat,

and force people to buy legitimate software,” he said.

“But I don’t see that happening right now.”

Source: China, Addicted to Bootleg Software, Reels From Ransomware Attack – The New York Times