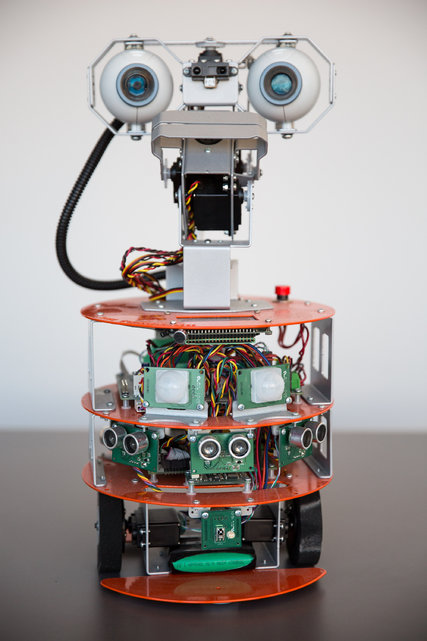

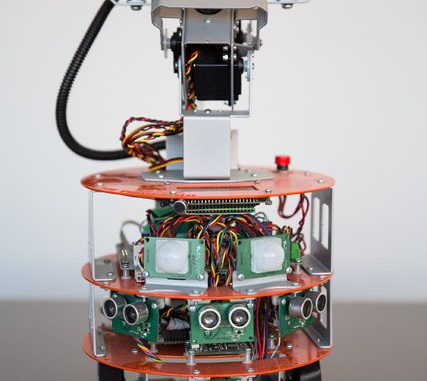

Chinese firms have significant investment in US start-ups working on cutting-edge technologies with potential military applications. The start-ups include companies that make rocket engines for spacecraft, sensors for autonomous navy ships, and printers that make flexible screens that could be used in fighter-plane cockpits. Many of the Chinese firms are owned by state-owned companies or have connections to Chinese leaders. Top, Neurala, an artificial intelligence start-up, which received an undisclosed sum from an investment firm backed by a state-run Chinese company, created software for this TurtleBot robot. Some start-ups, especially those making hardware rather than money-drawing mobile apps, said Chinese money was sometimes the only available funding. Bottom, Neurala’s Boston office.

When the United States Air Force wanted help making military robots more perceptive, it turned to a Boston-based artificial intelligence start-up called Neurala.

But when Neurala needed money, it got little response from the American military.

So Neurala turned to China, landing an undisclosed sum from an investment firm backed by a state-run Chinese company.

Chinese firms have become significant investors in American start-ups working on cutting-edge technologies with potential military applications.

The start-ups include companies that make rocket engines for spacecraft, sensors for autonomous navy ships, and printers that make flexible screens that could be used in fighter-plane cockpits.

Many of the Chinese firms are owned by state-owned companies or have connections to Chinese leaders.

The deals are ringing alarm bells in Washington.

According to a white paper commissioned by the Department of Defense,

Beijing is encouraging Chinese companies with close government ties to invest in US start-ups

specializing in critical technologies like artificial intelligence and robots to advance China’s military capacity as well as its economy.

The white paper, which was distributed to the senior levels of the Trump administration last last month, concludes that

US government controls that are supposed to protect potentially critical technologies are falling short,

according to three people knowledgeable about its contents, who spoke on the condition of anonymity.

“What drives a lot of the concern is that China is a military competitor,”

said James Lewis, a senior fellow at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, who is familiar with the report.

“How do you deal with a military competitor playing in your most innovative market?”

The Chinese deals can pose a number of issues.

Investors could push start-ups to strike partnerships or make licensing or hiring decisions that could expose intellectual property.

They can also get an inside glimpse of how technology is being developed and could have access to a start-up’s offices or computers.

Neurala created software for this TurtleBot robot. Some start-ups, especially those making hardware rather than money-drawing mobile apps, said Chinese money was sometimes the only available funding.

Trump administration officials and lawmakers are raising broad questions about China’s economic relationship with the United States.

While the report was commissioned before Trump took office,

some Republicans have called for tighter regulation of foreign takeovers by giving a broader mandate to the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States.

Known as Cfius, the committee reviews foreign takeovers of American companies,

but critics say its scope does not include smaller deals and that it has other weak spots.

Ashton B. Carter, former secretary of defense under President Barack Obama,

had tapped Mike A. Brown, the former chief executive of Symantec, the cybersecurity firm,

to lead the inquiry into the Chinese investments,

according to two of the people aware of the white paper’s contents.

The size and breadth of the deals are not clear because start-ups and their backers are not obligated to disclose them.

Over all, China has been increasingly active in the American start-up world, investing $9.9 billion in 2015, more than four times the level the year before,

according to data from the research firm CB Insights,

Neither the high-tech start-ups nor their Chinese investors have been accused of wrongdoing, and experts said much of the activity could be innocent.

Chinese investors have money and are looking for returns,

while the Chinese government has pushed investment in ways to clean up China’s skies, upgrade its industrial capacity and unclog its snarled highways.

Proponents of the deals said American limits on technology exports would still apply to American start-ups with Chinese backers.

But the fund flows fit China’s pattern of using state-guided investment to help its industrial policy

and enhance its technology holdings, as it has recently done with semiconductors.

China has also carried out efforts to steal military-related technology.

Still, some start-ups — especially those making hardware rather than money-drawing mobile apps like Snapchat — said

Chinese money was sometimes the only available funding.

But even a company struggling for money can ultimately come up with a big breakthrough.

Chinese investors have a bigger appetite for risk and a willingness to do deals fast, said Neurala’s chief executive, Max Versace.

Chinese investors have a bigger appetite for risk and a willingness to do deals fast, said Neurala’s chief executive, Max Versace.

To demonstrate his software’s capabilities to the Air Force, Versace said,

Neurala used its software on a ground drone from Best Buy to make it recognize and follow around the service’s secretary, then Deborah Lee James, during a meeting.

“We were told by the secretary of the Air Force,

‘Your tech is awesome, we should put it everywhere,’” he said.

“No one followed up.”

Neurala finally took a minority investment from a Chinese fund called Haiyin Capital as part of a $1.2 million round, Versace said.

He did not disclose the size of Haiyin Capital’s commitment.

Haiyin Capital is backed by a state-run Chinese company, Everbright Group,

according to a statement from one of its subsidiaries.

American military officials have “figured out a very good way to give $10 billion to Raytheon,” he said.

“But to give a start-up $1 million to develop a proof of concept? That’s still very, very hard.”

Late last year, a research firm called Defense Group Inc. argued in a report prepared for Congress that

the Neurala investment could give China access to the company’s underlying technologies.

It also said the deal could create enough uncertainty that US officials would steer clear of Neurala’s technology,

effectively wasting any American money that had gone into the firm.

Versace of Neurala said the company took pains to ensure that the Chinese investor had no access to its source code or other important technological information.

To address concerns that it was not tapping innovations from start-ups,

the Pentagon in 2015 set up a group called Defense Innovation Unit Experimental to enable investments into promising new companies.

While at first it struggled, in 2016 it helped carry off a barrage of deals.

The unit also prepared the white paper.

In May 2015, Haiyin Capital also invested an amount it did not disclose in XCOR Aerospace,

a Mojave, Calif., commercial space-travel company that makes spacecraft and engines, and has worked with NASA.

XCOR did not respond to requests for comment.

Haiyin Capital also invested an undisclosed amount in XCOR Aerospace, a Mojave, Calif., commercial space-travel company that makes spacecraft and engines and has worked with NASA.

In an interview in Chinese media, Haiyin Capital’s founder, Yuquan Wang, said that

part of its goal is to build Chinese industrial capabilities

and that it can be hard to get space technology into China because of US export controls.

About the fund’s investments, Wang said,

“We strive to get a portion of research and development moved back to China so that we can avoid China being only a low-end manufacturer.”

Haiyin Capital did not respond to a request for comment.

Quanergy, a company that works on the light-detecting sensors used in driverless cars, raised financing last summer

that included funds from the partly state-backed Chinese venture fund GP Capital.

A few days later, Quanergy purchased people-tracking software from Raytheon for an undisclosed amount.

Alongside a wide array of commercial technology, it makes sensors for military driverless vehicles

and a security system billed as “the most complete and intelligent 3-D perimeter fencing and intrusion-detection system.”

Quanergy did not respond to requests for comment.

Its investors also include foreign automakers and South Korea’s Samsung.

Chinese investors have also made a push in another industry, flexible electronics.

The technology, which the National Research Council has said is a priority for the American military,

can help make electronics lighter and easier to attach to anything, from a uniform to an airplane.

In 2016, a Silicon Valley start-up called Kateeva that makes machines that print flexible screens raised $88 million from a group of Chinese investors.

Three took board seats, including Redview Capital, a spinoff of a firm run by the former Chinese premier Wen Jiabao’s son, Wen Yunsong.

Kateeva’s chief executive, Alain Harrus, said that while investors in Silicon Valley had begun looking more at hardware companies,

raising big rounds for capital-intensive technology can be tough.

Kateeva ultimately raised money where its customers were — China and South Korea.

Harrus said he believed more should be done in America to figure out the best way to nurture and fund core next-generation technologies.

In the past six months, said Ken Wilcox, chairman emeritus of Silicon Valley Bank,

he had been approached by three different Chinese state-owned enterprises

about being their agent in Northern California to buy technology, though he declined.

“In all three cases they said they had a mandate from Beijing, and they had no idea what they wanted to buy,” he said.

“It was just any and all tech.”

Source: China Bets on Sensitive U.S. Start-Ups, Worrying the Pentagon – The New York Times